Church Saint Mary-Magdeleine / Mase / Valais / Switzerland / 1983-1985

Context

The existing church built in 1910 had important structural problems due to an inappropriate carpenter work and missing foundations just above an ancient cemetery. The tower parts were from different period since 17th century.

An architectural competition was organized to define the intervention type,

Concept – I love my Grandma with her wrinkles, please don’t lift her !

The intervention is based on a postulate: Architecture is the formal and meaningful expression of the history.

It proposes to recognize the cultural mutations and to affirm them according two typologies. After verifying the sites features to receive and give, the project will develop according the invariants (center and axe) and on the significant and witness relations of the building story then of the history.

the intervention can be defined as follow:

- Conservation of the sign: (memory)

- Introduction and expression of the modern liturgical space (concentric static) in the structure of the latin space: (linear dynamic).

This text observes, on one side, some general principle defining the design process and on another side of personal design interpretations. Daring this provocative title is I thing, pointing vulgar part of the restauratrice options of the current practice.

Architecture is the formal expression of the History

It involves that each period must be expressed by and with is built and natural environment ; this by the architectural intervention , without systematic subordination to supposed absolute values of the existing context. It is then interesting to define from the problematic and through a critical analysis, the meaning and the nature of those relations with the context. This analysis as well as the whole architecture process doesn’t operate in a linear vway, but also according the thought schemes through the successive project verifications and relations.

However it may be simply defined as follow:

the reading of the territory

the site, a built promontory, (socle) in the forefront of the village, dominating the val of Herens. The existing silhouette has a value as a sign, a landmark, the part of the wide landscape, important element of the memory: a watched/watcher position, appropriate to communicate far away.

the eyes of the history

the history is present as awareness. It doesn’t serve to deduct architectural forms, but to understand the evolution of the Christian space and its components…le centre and the axe. Combined since the roman basilicas and subordinated one to each other, along the the history of the religious architecture, generating by their properties so much meanings, they constitute and define two possible typologies of churches:

- the church with longitudinal plan.

- the church with central plan.

Once the the site features recognized and the axial/central typologies rediscovered, it’s from those invariants that the project will be made; excluding all barbaric shapes which would not be legitimate. We are then reducing to a defined case the infinite number of possibilities.

The conservation of the sign…It recognizes the physical, structural of the building belonging to the collective memory. It also recognizes the building effort and it’s particularly to recognize the longitudinal typology (the processional journey) as conditioning the actual experience of the religious practice. We observe then that the object it’s not the main interesting thing, but rather the essence of the relation between the parts, the semantic dialogue, the game of old and new relations, the intensity of the exchanges and the resulting emotions issues of the difficult balanced union. The project will become consistent by the material technologies for the form within the relations preliminarily defined. The materials, the textures, the light serve the relations. Assuming the cultural mutations by the container/content we recognize the building history instead of its historicity. It’s not here matter of progress on the past but rather another way for the history of architecture to exist in the present. So, at the time of the « re-plastering hysteria” and other epidermic treatments downgrading monuments, mummifying their memories, it’s legitimate to recognize architecture and history associating them, instead wasting desperately wasting their last chances.

Christian Beck in « nos monuments d’art et d’histoire » avril 1984

Church Saint Mary-Magdeleine / Mase / Valais / Switzerland / 1983-1985

written by ChristianBecK about the original project

Context

The existing church built in 1910 had important structural problems due to an inappropriate carpenter work and missing foundations just above an ancient cemetery. The tower parts were from different period since 17th century.

An architectural competition was organized to define the intervention type,

Concept – I love my Grandma with her wrinkles, please don’t lift her !

The intervention is based on a postulate: Architecture is the formal and meaningful expression of the history.

It proposes to recognize the cultural mutations and to affirm them according two typologies. After verifying the sites features to receive and give, the project will develop according the invariants (center and axe) and on the significant and witness relations of the building story then of the history.

The intervention can be defined as follow:

- Conservation of the sign: (memory)

- Introduction and expression of the modern liturgical space (concentric static) in the structure of the latin space: (linear dynamic).

This text observes, on one side, some general principle defining the design process and on another side of personal design interpretations. Daring this provocative title is I thing, pointing vulgar part of the restauratrice options of the current practice.

The architecture is the formal expression of the History

It involves that each period must be expressed by and with is built and natural environment ; this by the architectural intervention , without systematic subordination to supposed absolute values of the existing context. It is then interesting to define from the problematic and through a critical analysis, the meaning and the nature of those relations with the context. This analysis as well as the whole architecture process doesn’t operate in a linear vway, but also according the thought schemes through the successive project verifications and relations.

However it may be simply defined as follow:

the reading of the territory

the site, a built promontory, (socle) in the forefront of the village, dominating the val of Herens. The existing silhouette has a value as a sign, a landmark, the part of the wide landscape, important element of the memory: a watched/watcher position, appropriate to communicate far away.

the eyes of the history

the history is present as awareness. It doesn’t serve to deduct architectural forms, but to understand the evolution of the Christian space and its components…le centre and the axe. Combined since the roman basilicas and subordinated one to each other, along the the history of the religious architecture, generating by their properties so much meanings, they constitute and define two possible typologies of churches:

- the church with longitudinal plan.

- the church with central plan.

Once the the site features recognized and the axial/central typologies rediscovered, it’s from those invariants that the project will be made; excluding all barbaric shapes which would not be legitimate. We are then reducing to a defined case the infinite number of possibilities.

The conservation of the sign…It recognizes the physical, structural of the building belonging to the collective memory. It also recognizes the building effort and it’s particularly to recognize the longitudinal typology (the processional journey) as conditioning the actual experience of the religious practice. We observe then that the object it’s not the main interesting thing, but rather the essence of the relation between the parts, the semantic dialogue, the game of old and new relations, the intensity of the exchanges and the resulting emotions issues of the difficult balanced union. The project will become consistent by the material technologies for the form within the relations preliminarily defined. The materials, the textures, the light serve the relations. Assuming the cultural mutations by the container/content we recognize the building history instead of its historicity. It’s not here matter of progress on the past but rather another way for the history of architecture to exist in the present. So, at the time of the « re-plastering hysteria” and other epidermic treatments downgrading monuments, mummifying their memories, it’s legitimate to recognize architecture and history associating them, instead wasting desperately wasting their last chances.

Christian Beck in « nos monuments d’art et d’histoire » avril 1984

Kirche Sankt Maria-Magdalena / Mase / Wallis / Switzerland / 1983-1985

Jeder Eingriff an einem Gebäude erfolgt nach der Annahme, dass Architektur eine formale, bedeutungsvolle Ausdrucksweise von Geschichte sei. Er gigt vor, die kulturellen Äderungen zu kennen und sie nach den zwei möglichen Kirchentypen (longitudinal und Zentral) durchzuführen. Nach Überprüfung der spezifischen Eigenschaften eines Ortes wird sich das Projekt entsprechend den Konstanten (Zentrum und Achse) und den Zusammenhängen entwickeln, die in der Geschichte des Bauwerks und somit auch in der allgemeinen Geschichte verwurzelt sind. Der Eingriff kann wie folgt beschrieben werden:

- Erhaltung des Zeichens (Gedächtnis);

- Der moderne liturgische Raum (konzentrisch, statisch) soll in die Struktur des lateinische Kreuzes (linear, dynamisch) Eingang finden.

Chiesa Santa Maria-maddalena / Mase / Vallese / Svizzera / 1983-1985

Ogni intervento su di un edificio avviene secondo il presupposto: L’archittetura é l’espressione formale e peculiare della storia. Essa propone di individuare le riforme culturali e di affermarle attenendosi, nel caso si tratti di edifici ecclesiastici, alle due soluzioni tipologiche possibili (a pianta longitudinale e centrale). Dopo aver esaminato l’idoneità del luogo a dare e a ricevere, il progetto si svilupperà in base alle cosanti (centro e asse) e alle relazioni specifiche dettate dalla storia del monumento, e quindi della storia stessa. L’intervento può quindi essere descritto come segue

- Conservazione del segno (memoria);

- Introduzione ed espressione dello spazio della liturgia moderna (concentrica, statica) nella struttura a croce latina (lineare, dinamica).

Il lavoro qui presentato è il seguito di un concorso indetto nel 1983 mirante ad individuare il tipo di intervento possibile in un delicato contesto architettonico come la chiesa di Mase. La costruzione originale, infatti presentava preoccupanti deficienze di ordinestrutturale direttamente legate sia all’assenza di fondazioni e di drenaggio, sia alla inadeguatezza di tutto il sistema statico della carpenteria del tetto. Dal progetto di concorso scarturiscono due tematiche prioritarie: la coservazione del segno (memoria) e l’introduzione e la conseguente espressione della spazio liturgico moderno (concentrico e staico) nella struttura esistente (linerare e dinamica).

Questo concetto semantico propone di associare all’asse esistente (navata) un centro (rapresentato dal nuovo spazio cilindrico) alfine di realizzare lo spazio di comunione secondo le direttive del Concilio vaticano II. Dal punto di vista costruttivo la nuova struttura portante è composta da pilastri costituiti da un nucleo in cimento armato rivestito da mattoni di cemento. La nuova carpenteria è rimata da 6 capriate in legno. Il frontone e la parte superiore dell’arco trionfale sono reallizati con due muri paralleli legati tra loro con tiranti. La corpetura del tetto è in lamiera zincata. Il resulto finale è, comunque, molto distante dal progetto iniziale.

La parocchia di Mase infatti, “incoraggiata” dalle diverse commissioni cantonali, dopo aver scelto una soluzione sicuramente coraggiosa, ha assunto, durante l’iter di costruzione, una sempre maggiore attitudine “retrograda” in netto contrasto con l’immagine progettuale originaria.

L’architetto risulta quindi non essere l’autore di ulteriori opere quali il cimeterio, i materiali di rivestimento, la porta, l’arredo liturgico ed il soffitto.

L'EGLISE SAINTE MARIE - MADELEINE A MASE (VALAIS)

lecture critique de Bernard Gachet

.

C'est le temple qui, par son instance donne aux choses leur visage, et aux hommes la vue sur eux-mêmes.

Martin Heidegger (1)

La lecture et la critique de cet objet architectural sont le prétexte à quelques réflexions et interrogations sur la notion de sanctuaire :

celui-ci n'est-il pas le lieu où l'architecture démontre que "le sacré transcende le monde profane" (2)? Quel processus compositif y-a-t-il derrière l'oeuvre soumise au regard; comment un concept initial s'est-il développé et transformé ? Enfin, comment une construction contemporaine s'insère-t-elle à une partie déjà bâtie ?

L'église de Mase, partiellement reconstruite par l'architecte ChristianBeck est issue d'un concours d'idées lancé en 1983 dans tout le Valais.

Il s'agissait de proposer un principe d'intervention sur cette église bâtie en 1909, la nef menaçant de s'écrouler pour avoir été construite sans fondation ni drainage.

Trois options s'en dégagèrent : la reconstruction totale, la rénovation, et une construction nouvelle prolongeant certaines parties existantes.

Ces deux dernières furent retenues par le jury, et présentées au Conseil de Paroisse et de Fabrique de Mase, qui choisit la solution de reconstruction partielle (3).

Initialement, le projet prévoyait de glisser un cylindre de pavés de verre, transparent, sous la charpente de la nef, celle-ci étant, avec le choeur et le clocher, conservée.

Ce dispositif répond à deux préoccupations. La première, la silhouette générale de l'église n'est ainsi pas altérée. Elle est située sur un promontoire qui domine le Val d'Hérens, le chevet tourné vers la rue

principale du village. Ce signe, inscrit depuis des décennies dans lamémoire c ollective, est conservé. La seconde, l'architecte superpose un plan centré au plan basical. Ce choix répond à la nouvelle liturgie instaurée dès 1965 par Vatican II où le prêtre n'officie plus le dos aux fidèles, mais en face, voire au centre de la communauté religieuse.

Ce dispositif prolonge le débat qui s'instaura à la Renaissance ou le plan centré et le plan en forme de croix grecque s'opposèrent au plan en forme de croix latine. Ces deux types s'imposèrent dans de nombreuses églises, malgré les difficultés liturgiques que cela impliquait.

Bramante n'avait-il pas imaginé, pour le plan de Saint-Pierre, de superposer la coupole du Panthéon à la vieille basilique construite par Constantin, "montrant la prématie de Saint-Pierre et l'ancienneté de l'église Romaine" (4).

A Mase le processus s'inverse. Palliant à l'absence de coupole et de lanterne, où la lumière zénithale exprime un axe ontologique, le cylindre proposé est fait de pavés de verre translucides, nimbant d'une lumière uniforme l'espace interne du sanctuaire.

Affermissant le concept de centralité, l'autel se trouvait au centre du cercle, le choeur devenant une chapelle pouvant être utilisée (en semaine par exemple) indépendamment de l'espace central.

Cette organisation de l'espace (en adéquation avec la liturgie nouvelle !) fut refusée par le Maître de l'Ouvrage, au profit d'un dispositif plus traditionnel. Estimant, à juste titre, que cela dénaturait son

projet, l'architecte refusa d'y souscrire et son mandat fut révoqué.

Du concept initial, Christian Beck ne construisit plus que le cylindre de verre, la structure porteuse de la nef et la couverture, ces deux dernières étant en trop mauvais état pour être conservées. Les éléments

réalisés se présentent comme une ossature en béton armé enveloppée par une maçonnerie de plots de ciment que rythment de fines lignes horizontales blanches, les démarquant de la construction existante enduite d'un crépi.

La charpente apparente de l'édifice est recouverte d'une toiture en tôle. Le cylindre de pavés de verre s'enchâsse dans les piles d'angles. Il est renforcé, à

l'intérieur, par de fines colonnettes qui soutiennent la toiture plate en béton armé. La première travée de la nef devient le narthex de l'église, abritant le parvis.

Pour la commune de Mase, l'architecte redessina également le cimetière situé au sud de l'église, proposant un tracé régulier et une simple croix identique pour toutes les tombes. Il prolongea une tradition valaisane en voie de disparition, où l'absence de stèles, caveaux, etc..., montre l'égalité de tous devant la mort.

La conséquence de la mésentente entre le Maître d'Ouvrage et l'architecte fut l'attribution de la suite de l'exécution de l'ouvrage au bureau AMB SA, architectes à Sion. Il acheva le second oeuvre, la rénovation du choeur, de la sacristie et du clocher, le pavage extérieur, dessina le mobilier liturgique(5). Un autre architecte, M.

Couturier construisit le péribole et la morgue-chapelle ardente, qui reflète si peu la signification profonde de ce seuil ultime (6). Il est regrettable que ces architectes ne surent comprendre et interpréter la substance de la structure primaire déjà mise en place par Christian Beck. Comme le Maître d'Ouvrage qui, après un choix exemplaire au niveau du concours se cantonna dans une attitude rétrograde....

Cela laisse à celui qui visite l'église aujourd'hui, un sentiment amer de laisser-aller et d'incertitude.

Pourquoi le système spatial construit, c'est-à-dire l'adéquation entre l'espace, la structure et la lumière (7), n'a-t-il pu surmonter et dépasser les contingences ?

"Je dois réaliser des choses si fortes " disait L. Kahn, à propos du Palais de l'assemblée à Dacca et de ses utilisateurs,"qu'ils ne puissent plus avoir envie d'autres choses" (8).

Il semble que le concept initial est resté prisonnier de la figure, c'est-à-dire du cercle et de sa projection verticale, le cylindre. A partir du moment où la structure primaire de la nef était reconstruite,

ne fallait-il pas tout entreprendre pour renforcer cet espace centré ?

Or l'emploi de piles massives carrées et rondes rompt non seulement l'unité recherchée, mais impose une partition et une axialité au détriment de la centralité : les deux piles circulaires supportant la toiture flanquent de part et d'autre l'espace interne, et le tracé de la rotonde s'enchevêtre avec celui du choeur. Le dispositif est inabouti, incomplet.

A la Renaissance l'espace circulaire et centré connotent, aux yeux des concepteurs, du clergé et des fidèles, un univers parfait, achevé.

L'église est un microcosme, un reflet du macrocosme constitué de sphères emboîtées. La Connaissance de Dieu est envisagée à travers les mathématiques et la Science des Nombres. Développant alors une formule

pseudo-hermétique, Dieu est la plus parfaite figure géométrique, tout à la fois "centre, diamètre et circonférence du cercle" (9). Cette forme ne peut être subordonnée à aucune autre. La structure bâtie qu'elle implique ne peut être que rayonnante, rejetée à la périphérie, laissant à l'espace sa plénitude.

Ainsi, à l'église de Mase, le mur écran du choeur comme le système porteur de la nef aurait-il dû s'effacer, se tenir en retrait, rester aérien, laissant la jouissance totale de l'espace intérieur, libéré de toute entrave. La nef et sa charpente seraient ainsi devenues l'élément

médian dilatant l'espace vers le ciel. Mais ces deux colonnes renvoient peut être à une symbolique plus ancienne encore, à l'Axis Mutandis (10) qui se trouvaient dans les sanctuaires des sociétés archaïques. Dans ce cas l'architecte n'a-t-il pas voulu trop en dire, rendant, par l'excédent de significations, et par un manque de rigueur peut-être, la lecture et l'usage de l'oeuvre bâtie malaisée, voire obscure ?

Le lecteur est invité à visiter cette église, et poursuivre les pistes suggérées dans cet article car "passer de la lecture à la critique, c'est changer de désir, c'est désirer non plus l'oeuvre, mais son propre langage". (11).

Bernard Gachet

chargé de cours, ITHA

NOTES

1) Martin Heidegger, l'origine de l'oeuvre d'art, in Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part, édition Gallimard, Paris, 1962.

2) Mircea Eliade, architecture sacrée et symbolisme, in les symboles du lieu, Cahier de l'Herne n°44, 1983.

3) Bernard Attinger, Charles-André Meyer, Christian Beck, Restaurer outr ansformer ? le cas de Mase, Monuments d'Art et d'Histoire n°3, 1985.

4) Peter Murray, Architettura del Rinascimento, Electra Editice, Milan, 1978.

5) Cf. brochure, un siècle deux église-Mase.

6) L'information m'a été donnée par Christian Beck.

7) Comme le soulignait Christian Beck lors d'un récent entretien.

8) John W. Cook et Heinrich Klotz, Questions aux architectes, chapitre 6, édition Pierre Mardaga, 1974.

9) Pour de plus amples développements, se référer à l'ouvrage de R.Wittkower, Architectural principles in the Age of Humanism, Londres 1962, et plus particulièrement le chapitre intitulé : The religious

symbolism of centralled planned churches.

10) C'est à dire le pilier qui soutenait le ciel, passage médian entre les 3 zones cosmiques in Mircea Eliade, ibid. note 2.

11) Roland Barthes, Critique et Vérité, le Seuil 1966.

Lausanne, le 7 février 1991 BG/as

the context

the church on a promontory ahead of the village

topography

2 churches front each side of the valley.

evolution of the christian space from the roman basilica to vatican II.

typologies combine the axe and the center for the practice of the liturgy along the history.

concept

the axe & the center combine as the 2 components of the christian space, in order to:

-

conserve the existing sign (collective memory).

- introduce the centrality (new liturgy component).

the evolution of the christian space from the roman basilic to the new liturgy (1964)

photo: Irene Gutman

principle of typologies combination

schematic typology

photo:

Jean-Louis Pitteloud

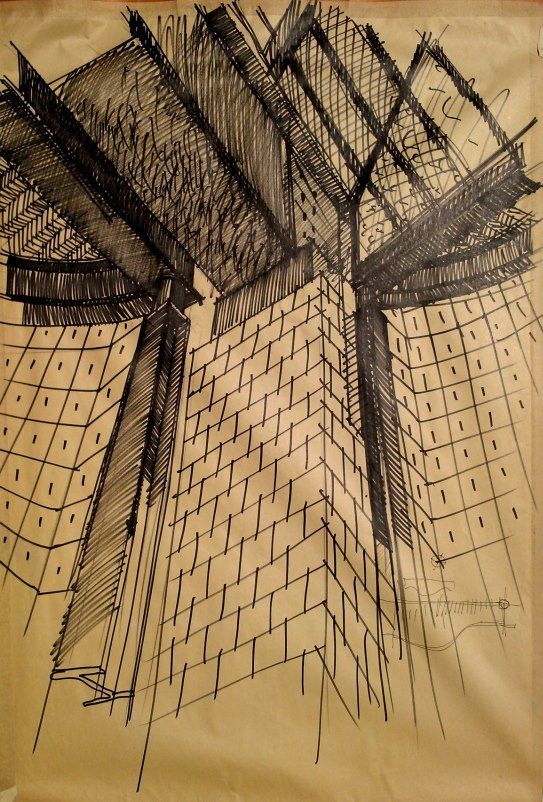

constructive and spatial researches

2nd preliminary project

transversal section

the church in 1983 before the transformation

The tower

the lower part exists from the 17th century.

It had been raised with the bell room in 1910 when the church was rebuilt on its other side.

the nave 1910-1985

1910-1985

the ceiling of the nave

the ceiling of the choir (maintained)

baptismal font

stained glass

photo:

Robert Hofer

photo:

Charly-G. Arbellay

photo: Irene Gutman

photo:

Charly-G. Arbellay

photo:

Charly-G. Arbellay

photo:

Jean-Louis Pitteloud

photo:

Jean-Louis Pitteloud

photo:

in Bilan...?

photo:

.....?